| Names: | Salapoika    |

|---|

Here, I want to touch on one of the most mysterious figures: Salapoika Väinämöisen "Secret son of Väinämöinen".

One might be surprised to see this mention in beginning of some South Ostrobothnian incantations: Väinämöinen, you committed adultery! Another surprise might be the "secret son of Väinämöinen" who is asked to use his sword from water to heal an abscess. He is also called the helper of the mythic saviour who rose from the sea. On the negative side, a nightmare is also called an illegitimate son lulled by Väinämöinen.

Väinämöinen isn't exactly described as a married man. What happened here? A Kainuian runosinger described Väinämöinen having a beautiful son who had become a great sorcerer (or tietäjä) and a skilled fisherman. He also made a shepherd's horn he used to summon bears, proceeding to then kill them. In this context, Väinämöinen is said to have a wife he gave fire to from his belt.

Väinämöinen's "wife" is also a bit of a mystery. A Savonian runosong states that Väinämöinen married the death goddess Louhi and they had a son, who she later sent to the northlands to get her inheritance. There, he faced the mighty shamans on the north in battle. Väinämöinen believed he couldn't make it, but he did. There is, however, no other mention of Väinämöinen marrying Louhi, though he did also attempt to get her in Kainuu.

More often, Väinämöinen's wife (akka) is connected to water. Once, he fished a salmon he tried to eat, but the fish jumped back into the water and revealed herself to be a water maiden. In Karelia, this song is followed by a description of how Väinämöinen was sad at not being able to get this maiden, but no such continuation has been collected from Finland. Some songs describe a woman by the sea brushing her hair, a bristle being cut from her brush, and this then becoming the snake which causes toothache. In another song from Karelia, this woman is specifically called Väinämöinen's wife. In Kainuu, Väinämöinen's wife is also involved with the toothache snake as it is born out of a bristle of her broom.

In face of this all, it's not surprising that Christfrid Ganander stated the mother of Väinämöinen's secret son is a sea maiden. Runosongs mention the name Väinätär but it's not certain if this means a wife of Väinämöinen, a daughter of Väinämöinen, or just some general water maiden with no connection to Väinämöinen (as väinä means "a streampool"). According to Ganander, the relationship between Väinämöinen and this "mermaid" was a "marriage of conscience" which I understand to mean a couple treating their relationship like a marriage even though it's not recognized or considered valid by the church. (Correct me if I'm wrong...)

One narrative of the birth of Väinämöinen's son can be found from runosongs inspired by Medieval ballads. However, even this narrative has to be pieced together from multiple different Finnish and Karelian runosongs. In the more known version, a maiden named Marketta is raped or otherwise impregnated by a man, and she abandons the child after it's born. Helena, who might or might not be Marketta's mother, finds the child and goes around asking from all the men and women who the parents of this child are; if the father is not found, the child is to be drowned, and if the mother is not found, it is to be burned. Then Jesus, Mary, God or all of them give the newborn the ability to speak, and it reveals the identities of the parents.

There is an instance where Väinämöinen is the father and Marketta is the mother, but this seems like a contamination between two different tales. Indeed, one of the reasons why it's so difficult to find the "original" tale of Väinämöinen's son is that it's been effectively mixed up with other Medieval ballads. One might think that Väinämöinen's Judgement, the runosong in question, can only be found from Karelia and is even born there; even I made this mistake before! However, 1) Forest Finnish runosongs show that this runosong used to be known in Savo, 2) South Ostrobothnian runosongs show Väinämöinen's adultery was known in Western Finland, 3) the words used in White Karelian versions of the runosong show it is of Finnish origin, not invented in Karelia (such as using the Finnish word laki for "law" instead of the Karelian word zakon).

A Forest Finnish runosong of the origin of frost includes the lines:

Isä pani Ilmariehtaroille Vel' Vennen Joukariksi Sisar Sotijaloksi Emä pani Pakkaisiksi |

Father named him Ilmariehtaro Brother Joukari of Venne Sister Sotijalo Mother named him Pakkanen (frost) |

How interesting. It displays family members debating on how to name a child. Names were chosen from ancestors, and same names tended to circle in the family; this was important, too. Ancestors were reborn into the family when a new member was named after them. Names had to stick too! And they didn't always do that at first. People could've changed their name multiple times in their life to find the proper, "correct" one. There were individuals whose duty it was to contact the ancestors to find a proper name for a newborn. It was serious business! Nowadays, parents just choose the name based on whatever, but it's still common to use a grandparents' name as a second or a third personal name for a child.

From this, we can peak at a White Karelian poem according to which father named someone Ilmarinen, mother Ehtolapsi ("Evening child"), sister Sotijalo and brother a "horde of Vento". Where this child came from, virgin birth or otherwise, varies and is usually loaned from other runosongs, ergo it is not important. After this, Virankannos is invited to come baptize the child, but he refuses to do this unless a proper name can be found. And a proper name cannot be found if the father of the child is not known. As nobody admits to being the child's father, Väinämöinen working as a judge sentences the child to be taken into the forest and killed by hitting it on the head with a club. What is to be understood here is that in the old days, it was seen as acceptable to kill a newborn child before it had been named and therefore made a member of the community.

That's the society you're fighting for, by the way, if you're anti-abortion!

Anyways, the 3-night or 2-week-old child magically gains the ability to speak and asks Väinämöinen why would he be judged when Väinämöinen himself had an incestuous relationship with his mother by the seaside. Ashamed by this, Väinämöinen sails away into a whirpool, and the child is crowned the king of Pohjola, or Metsola, or Karelia.

So, that made little sense! This story has been interpreted as a tale of Christianity arriving to Finland: the newborn is baby Jesus and he is able to drive away the pagan deity Väinämöinen. That's not really the whole truth, however.

When accusing Väinämöinen of incest, the child says: Makasit oman emosi "You lied with your own mother". However... this might be a corruption of the original, influenced by the tale of Sämpsä Pellervoinen and fertility increasing sexual relations with the Earth Mother. If we were to change one letter, the narrative would make a lot more sense. If the child said: Makasit oman emoni "You lied with my own mother", the narrative would become complete. Väinämöinen had out-of-marriage sexual relations with a water maiden, which resulted in the birth of this child. Väinämöinen, as the judge, tells the baby to be killed as the father is not known, but the child does the impossible and is able to reveal the truth: "why would I need to be killed for being fatherless when YOU are my father". Quite the reveal, and it certainly should embarrass Väinämöinen. However, if the Kainuian runosongs have any connection to this, they imply that Väinämöinen and this mermaid ended up raising this son after all, and he became a great tietäjä in his own right.

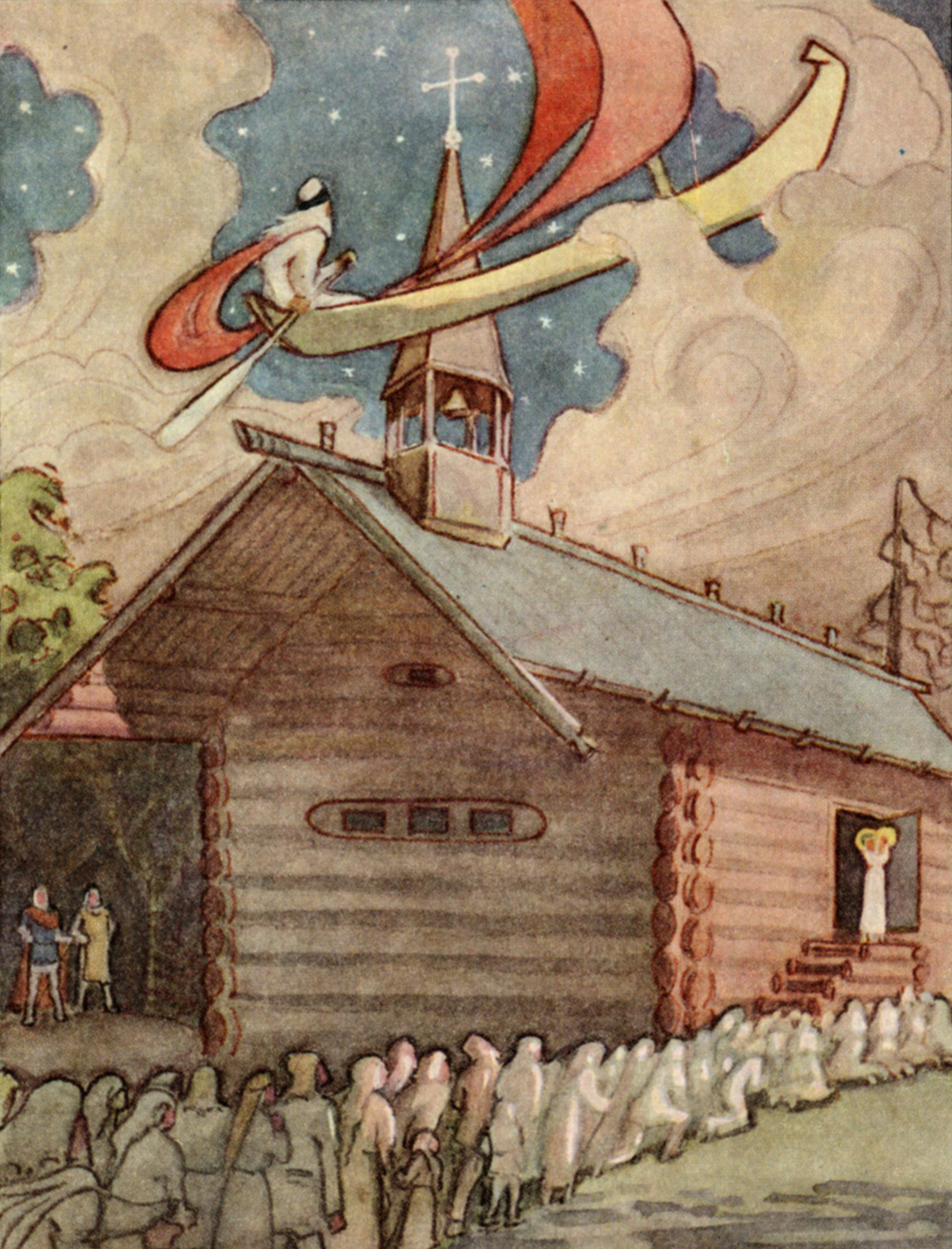

Some runosingers thought that when Väinämöinen sailed into the whirlpool, he died. Others argued that he was still alive and would return one day in true Arthurian fashion. According to mainly Western Finnish folklore, one or multiple sons of Kaleva left Finland with red boats or stones when Christianity and priests arrived. One account even claims that Väinämöinen created a skerry in Pirkanmaa as a stepping stone for himself as he was escaping from the Swedes. Maybe these tales got mixed with the initially unrelated one of Väinämöinen's "illegitimate" son.

And speaking of naming, what name was this child given in the end? The only clues we have about this are in a Karelian runosong stating that he was named Joukamoinen, but this name was not good for him. Then, he was named Kaukamoinen, and this name was good. So Kaukamoinen or Kaukomieli ("far-mind") it is? Not that this proves that Väinämöinen's son Kaukamoinen is the same sword-hero Kaukamoinen from some other runosongs. Other connections to Joukahainen (Väinämöinen's younger brother) are also interesting, as both him and Väinämöinen's son are connected to frost and the north... and Väinämöinen.

In fact, I wouldn't throw away the idea that Väinämöinen's son is somehow Frost itself, as frost is told in a runosong: "If you are of the family as the son of Osma (Kaleva) was, from the village in Ostrobothnia was Vänkämöinen, do not freeze me". And Vänkämöinen is in many cases seen as the same as Väinämöinen.

Kaukomieli and similar names were quite common in Finland at some point, as shown by historical records. According to the Icelandic Egil's Saga, a Norwegian chief named Thorolf Kveldulfsson teamed up with the King of Kvenland, Faravid, to fight against the Karelians. The nature of "Kvenland" is its own entire topic, but it's often assumed to be a Finnic land, practicing hunting, fishing and fur trade from the northern wilderness. "Faravid" is not a Norse name at all, so it has been assumed to be a translation from the Finnish Kaukomieli. As Väinämöinen's son here is named the "guardian of a fur mountain", Martti Haavio suggested that the Pohjola or Metsola he became the king of actually means Kvenland or "Kainuu". Not sure if I'd make such wild connections between mythological figures from entirely separate sources, though...

Forest Finnish runosongs bring up get another strange tale: Väinämöinen's arm was cut off on a turning wheel (a torture methos like the breaking wheel?) After this, Väinämöinen's secret son is asked to stop the bleeding. Could this have been a punishment for the extramarital affair? Bloodstopping is interesting anyways: the usual tale is that Väinämöinen hurts his knee while making a boat and goes around finding someone to stop the bleeding. Eventually, he finds a house where a child (sometimes as young as 3-nights-old) confirms that there is someone in the house who can help, and the otherwise unnamed master of the house uses his shamanistic skills to help Väinämöinen.

As stated earlier, it is sometimes difficult to say if some titles are referring to Väinämöinen, or just water in general. Same goes for the epithet Väinän tytär "daughter of Väinä" or "daughter of a streampool" (or a slow river). Kivutar is given this epithet, which is why Ganander called her Väinämöinen's daughter, but this is by no means certain: her home is, after all, at the confluence of three rivers. Väinä is also the Finnic name of the river Daugava in Latvia, Belarus and Russia: in Seto runosongs (a Finnic people), Väänä tütär means a woman living by the river Daugava.

The same question can be asked about Väinän poika "son of Väinä". Water is called older than iron or fire, and its origin is in a mountain. It was Väinämöinen who pulled water out of the mountain. Water is also called Vesiliito or Vesiviitta ("water cape") son of Väinä, and he is a helper of Väinämöinen in White Karelian runosongs. However, this does not necessarily mean that he is Väinämöinen's son: he is also called Suoviitta, Kalevan poika ("swamp cape, son of Kaleva") which would make him Väinämöinen's brother.

Only in Finnish, sorry. This is the source material.